Imagine pulling into a service station, starting the pump and then realizing you’re being charged not for how much gas you need but how long you’re hooked up to that pump. Well, that’s pretty much how things work right now if you use a public charger for an electric vehicle. At most U.S. stations you pay for the time you’re hooked up, not for how much energy you squeeze into your battery.

That’s beginning to change – in roughly half the country Electrify America charging stations will now charge for energy the same basic way you buy gasoline: by the kilowatt-hour, or kWh.

“Electrify America has listened to feedback from electric vehicle owners, potential customers, and longtime industry advocates. As a result we have developed a new pricing structure that is fair, consistent, and recognizes the increasing customer demand for kilowatt-hour pricing,” said Giovanni Palazzo, president and chief executive officer of Electrify America.

The idea of buying by the kWh might seem logical. After all, that’s how you do it at your home or office. But, with rare exception, that’s not how it works when it comes to purchasing energy on the road. With relatively rare exception, three of the four major public charging companies, along with many of the smaller firms, have charged for connection time, rather than the amount of energy you actually use.

(Electrify America launches home charger sales.)

That approach means that what you pay may have little to do with what actually gets pumped into your battery pack. That’s because different vehicles charge up at different speeds. Lucid, for example, claims it will be able to add as much as 20 miles a minute using the latest-generation quick chargers for the Air sedan coming to market next year. Other EVs can add range as slowly as three to four miles a minute.

And even with the same vehicle a variety of factors can impact how quickly it charges up. Temperature plays a critical role, especially when both the battery pack and ambient air temps are low. When TheDetroitBureau.com plugged a Jaguar iPace into an EVgo charger near Detroit during a polar vortex last winter it took an hour to add just 80 miles of range but cost over $16. At that price, it was significantly more expensive than what a similar Jaguar F-Pace would have cost to operate on gasoline.

Meanwhile, charging companies have been staggering costs depending upon the type of charger they have. There are now three standards for public fast chargers: 50, 150 and 350 kilowatts. To use the most powerful, some energy providers are socking customers at more than $1 a minute in some locations.

(Electrify America, Bank of America plan to let you charge up where you bank.)

Public charging companies such as EVgo, ChargePoint and Electrify America are not necessarily the ones to blame, however. Until recently, that’s how most states required them to operate. That’s changing fast under pressure from consumers and EV proponents who see the sometimes outlandish approach of timed pricing as an obstacle to broader acceptance to public adoption of battery-electric vehicles.

West Virginia recently became the 30th state to permit charging by the kWh but some others continue to resist the change.

West Virginia recently became the 30th state to permit charging by the kWh but some others continue to resist the change.

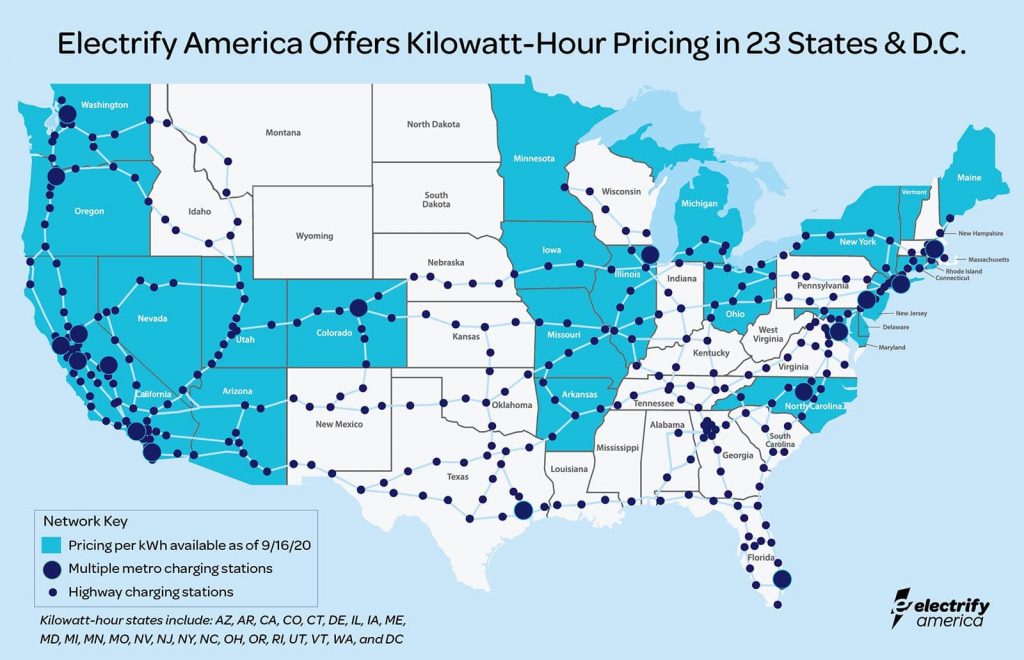

Electrify America, the charging company backed by Volkswagen as part of its settlement of the diesel emissions scandal, is switching to a per-kWh model in 23 states and the District of Columbia. The company, which is still in the early stages of rolling out a national network, says that will cover “more than 78% of charging on the Electrify America network.”

Pricing will vary from one location to another, much as is the case with gasoline, and could be influenced by factors such as what the company pays locally to utilities and possibly even by time of day. The lowest will be 31 cents per kWh, Electrify America said.

Other charging companies are starting to make the switch, as well. Tesla has generally followed the direct pricing approach where state law allows and offered energy for as little as 28 cents per kWh. ChargePoint does not directly operate its stations, instead supplying technology to private owners who can choose what model to follow, where permitted, as well as how much to charge by the minute or kilowatt-hour.

(ChargePoint raises $127 mil from investors to expand operations.)

At 30 cents or so, public chargers are clearly more expensive than refilling a battery at home where most U.S. consumers pay around 14 cents per kWh – and where many EV owners can access timed tier pricing that can drop as low as a few cents per kilowatt-hour at off-peak hours.

That, the lack of public chargers and the convenience of charging at home or office explains why about 80% of EV charging takes place at home – and why Pat Romano, the CEO of ChargePoint, expects that to continue going forward.

But there’s also the convenience of not having to worry about being able to get back home or to your office to recharge. And, as more EVs come to market, many sold to buyers who won’t have access to their own chargers, public stations are becoming critical. They’ll also be essential for those taking long trips, as well as EV operators who run up extensive mileage. Uber and Lyft, for example, want their independent contractors all to switch to battery-electric vehicles by 2030.

(Tesla wants to go solar at many Supercharger locations.)

Using public charging means someone with a 60 kWh pack in a vehicle like the Chevrolet Bolt EV would spend about $18 to refill a fully drained battery. At home that might vary from a couple dollars using off-peak rates to more than $8 during regular hours. With an EPA-estimated range of around 240 miles, that would work out to around 7.5 cents a mile using energy from the public charger – but anywhere from 1 to 4 cents when charged at home.

By comparison, a compact hatchback with a combined mileage rating of 28 mpg costs about 7.1 cents per mile. So, EVs charged at home operate at a bargain. Those using public chargers will run at roughly the same cost per mile as comparable gas vehicles. And, as with any vehicle using an internal combustion engine, energy efficiency varies from one model to another.