If there is one styling cue that would come to symbolize post-war American exuberance, it’s the tailfin, which debuted this week in 1948 on the Cadillac’s Sixty Special. And while fins seemed radically new and modern at the time, it was not a new idea, although how they were deployed was.

The honor for the first car with a tailfin, albeit a single, center-mounted one, is the Czechoslovakian-built Tatra T77 of the 1930s. But their birth on Cadillacs — concept cars — dates to 1941.

A new styling concept

It was then that General Motors design chief Harley Earl, along with designers Bill Mitchell, Franklin Q. Hershey, and Art Ross among others saw the then-secret Lockheed P-38 “Lightning” fighter aircraft powered by two Allison engines.

“Earl knew the commandant out at Selfridge Field,” said Bill Mitchell. “He arranged for us to go out and see one of the first P-38s.”

It proved an inspiration for the group, which was charged with conceiving ideas for postwar styling. Back at GM’s design studios, Designers Paul Mochel and Ed Glowacke were so taken with the plane, they hung banners hailing twin tailfins.

Earl was smitten as well, assigning Franklin Q. Hershey with generating concept vehicles inspired by the plane’s design elements, including its pontoon front fenders, pointed nose, curved windshields and, most notably, its tailfins. The result was a series of 3/8 scale models that were named the Interceptor Series, many sporting tailfins.

Deep roots in car design

As car designers go, most know about Franklin Quick Hershey, born in 1907 in Detroit. Hershey’s first job was Walter M. Murphy Co. in Pasadena, California where he worked on the Peerless Sixteen. When Murphy shut down, Hershey was named chief of design at Hudson. “I just didn’t feel at home at Hudson and, fortunately, after about two months I got a call from Harley Earl to come to GM to run the Pontiac studio,” Hershey recalled in a letter to Collectible Automobile magazine in 1995.

Once at Pontiac Design studio, Hershey endowed Pontiac with its famous silver streak design. He would run the studio through 1940.

But Hershey, having started the Interceptor series, would be called up for military service, returning to GM Design in 1944, where he picked up development of the Interceptor project with help from designers Art Ross and Ned Nickles.

By 1945, he was promoted to run the Cadillac Design studio and charged with bringing one of the concepts to production. He also brought his fondness for tailfins. But the assignment wouldn’t last long. In May 1945, Hershey was assigned to run GM’s European design operations, which then included Vauxhall and Opel. Art Ross took his place until Bill Mitchell returned home to GM after serving in the Navy, whereupon he was named head of Cadillac design in November 1945.

The car they created

The car Mitchell was working on featured fairly radical styling, with wraparound front bumpers and enclosed front wheel arches. But Earl changed his mind, and Mitchell had to scramble to get a front-end design approved and ready for production with less than two years until production was scheduled to begin.

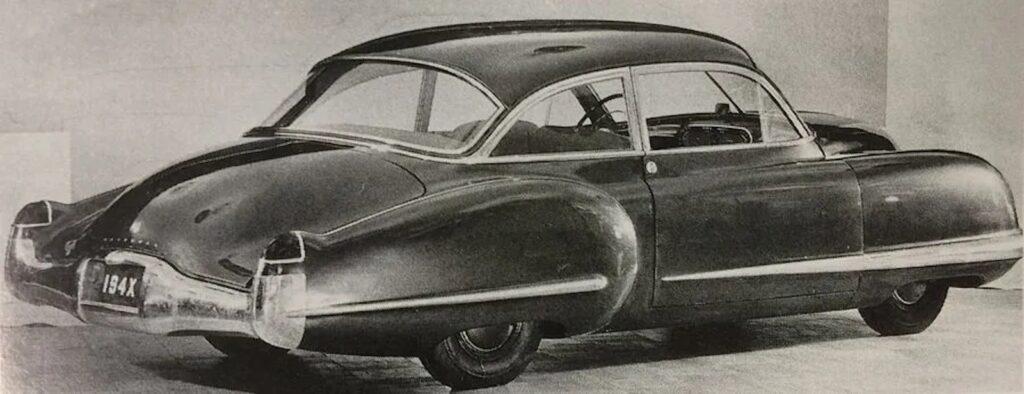

In the meantime, the mercurial Earl reassigned Hershey yet again, this time to create a special car for Cadillac codenamed CO. The resulting slab-sided concept featured wraparound bumpers, enclosed front wheel openings and tailfins. Meanwhile, GM engineers were finalizing the B and C body platforms as Mitchell was putting the finishing touches on the 1948 Cadillac, one that be the first to feature a Cadillac trademark that would endure for decades in various forms: the tailfin.

A styling solution

Mitchell was adept at making Earl happy. Earl’s mantra was simple: “Give us something new,” he would say. ”We’ll figure out how to build it.”

But the tailfin was seen by designers as solving a number of visual problems. It lowered the visual height of the upper portion of the car. It also helped prevent the car from looking shorter than it was, a problem with cars that had rear fenders that curved inward.

“From a design standpoint, the fins gave definition to the rear of the car for the first time,” Mitchell later said. “They made the back end as interesting as the front, and established a longstanding Cadillac-styling hallmark.”

When the new vehicles arrived, they were offered as a Series 61 or 62 coupe, sedan and convertible as well as Fleetwood Sixty Special and Seventy-Five bodies.

As for the CO, GM management thought the car was too radical for production, so it was never built. Hershey would end up leaving GM to work for Ford Motor Co., where he would create the 1955 Ford Thunderbird among many other models.

Earl had chosen Hershey as his successor, but Hershey would never return to GM. He died in 1997. But the design he created would become a Cadillac hallmark, one that was be widely copied throughout the industry. But more than that, it became a cultural touchpoint, coming to embody the exuberance of 1950s America.