As the push toward a carbon neutral environment continues, the automotive industry’s role in that shift continues to be heavily scrutinized.

Every so often, someone proposes using synthetic fuels as a cleaner alternative to standard gasoline and petroleum (not bio) diesel fuel and perhaps a less costly option compared to electric vehicles. Often those proposals come with criticism of the federal government’s push toward selling more EVs, which are currently more expensive than vehicles powered by internal combustion engines.

Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Michael Regan recently pushed back while introducing the newly proposed emissions rules, claiming the new rules were designed to give automakers plenty of ways to reduce emissions.

“This creates a conversation for hydrogen fuel cells, electric vehicles,” he said, “we can look at different variations of new fuel sources that we might have moving forward. I think we’re giving the automobile industry options to choose from.”

Hydrocarbon-based options

Porsche, in particular, has invested heavily in developing synthetic hydrocarbons, but it is joined by many companies in the traditional oil industry such as Repsol, Royal Dutch Shell, Phillips 66, ExxonMobil, McLaren and Bosch.

The basics are simple enough. You need to produce a liquid hydrocarbon that will burn like gasoline or diesel fuel. Some synthetics are plant-based, essentially refining the oils in the plants to produce diesel fuel, typically, but they can also produce gasoline-like fuels.

Bio-diesel has been popular in various concentrations for most of the past 20 years, and is commonly accepted as a replacement for petro-diesel, at least in warm climates.

Porsche leads on synthetic gas

However, the research and development taking place at Porsche is focused on a process that takes carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and creates new fuel that is a direct replacement for gasoline.

“We will only meet our ambitious decarbonization goals if we factor currently existing vehicles into the decarbonization effort and operate them as close to net carbon neutral as possible,” said Karl Dums, Porsche’s team leader for synthetic fuels.

“Worldwide, there are roughly 1.3 billion vehicles with combustion engines, so we’ve developed various different ideas for operating combustion engines as near to net carbon neutral as possible.”

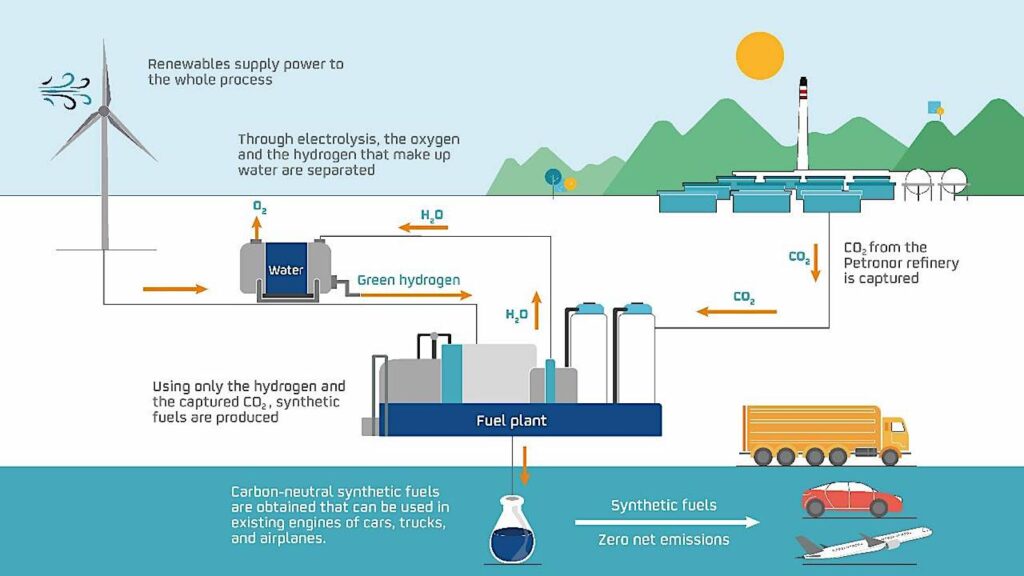

Synthetic fuels under development are made by using electricity generated by wind or solar power to split water molecules into their component hydrogen and oxygen atoms. The hydrogen is then combined with carbon dioxide harvested from the atmosphere to produce methanol, which can be further refined into gasoline, or into diesel or jet fuel if desired.

“In their fundamental properties, they are no different than kerosene, diesel or petrol produced from crude oil,” according to Dums.

This process is not terribly complicated, and it is the same technology in use by Repsol and other players to create synthetic fuels. But it is energy-intensive, requiring dramatically more energy input to create than you can get back out of the fuel.

Big energy input, net-zero CO2 emissions

If you take a step back, the synthetic fuel process simply takes carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere, mixes it with hydrogen and burns the resulting fuel, releasing the same carbon dioxide back into the air.

That’s a greenhouse gas win compared to burning more fossil fuels, but there are opportunity costs as well.

For example, it takes a lot of electricity to split water molecules using electrolysis. A rough estimate is that it takes about 11 megawatt hours to produce 300 gallons of methanol through electrolysis of water and recombination with carbon dioxide. That’s enough electricity to power about 2,000 standard homes for a day. Oh, the United States currently uses about 369 million gallons of gasoline every day. So the math is challenging, to say the least.

Even assuming that we produce that electricity through renewable means, it might be more efficient to use the electricity to power EVs directly. Then after electrolysis has produced hydrogen, it might end up being more efficient to use that hydrogen to generate electricity for an EV in a fuel cell.

Finally, there’s the issue of cost. As late as 2020, Porsche CEO Oliver Blume estimated the cost of its synthetic fuels at about $37 per gallon. More recent estimates have brought the cost down as low as $5-$12 per gallon. But to a population accustomed to paying much less than that for the low-hanging fruit of petroleum products, that’s also likely to be a non-starter.

Still in the early stages

Going through all this, you might think that synthetic fuel is a dead end. But it’s important to remember that research and development are in early stages, and the potential is there for large-scale solar facilities around the world to produce enough electricity for home and industrial use, as well as EVs and synthetic fuel creation.

Moreover, the ability to use unpopulated desert regions for electricity and synthetic fuel generation would change the political dynamics of petroleum. Widespread development of synthetic fuel would be detrimental to nations that currently control large petroleum and natural gas reserves, such as Russia and the OPEC nations. Currently impoverished nations with a great deal of sunshine, including many in Africa and South America, could become new fuel and energy suppliers to the world.

It may be some time before you pull up to a synthetic fuel pump, but synthetic fuels are likely to be part of the overall transportation and energy solution in the years to come. In particular, they will offer a lifeline to older gas-powered classic vehicles as fossil fuels are phased out entirely.

I agree that using the hydrogen in a fuel cell is a better option, but if they can really produce gasoline for $5-12 a gallon it may be a lot better that having to tear up the earth making batteries and the occasional fire that takes down your house and family.

Alternatives are always welcome.

“If everybody is thinking alike, then somebody isn’t thinking.”